It's been a while since the last update. .NET 6.0 LTS is already available for all supported platforms, so now Retro Assembler is built for .NET 6.0 and the purely Windows version is still built for .NET Framework 4.8

There's not much change in the assembler itself, but I found some bugs in the expression evaluator and fixed those.

See the documentation for details.

Download the latest version from the Retro Assembler page!

It's been a while since I posted about the Ariel Virtual Computer project. A lot happened to it since then, and also, not so much. Unfortunately, I've fallen into the trap that keeps many projects getting from the prototyping stage (if there was one) to completion: Scope Creep. It's a technical term for including more and more features in a project, compared to the modest, down to earth initial design plan and things just get out of hand. I'm not completely lost though, but it's time for me to take a step back and make some level headed decisions about what's next.

The virtual machine (or emulator, same thing) that's running behind the scenes has been more or less done back then, I just fiddled around with it to cut out some unnecessary capabilities. This part of the project is surprisingly solid. If you'd like to look at some of the CPU details, I created a PDF file that I use as a cheat sheet while writing assembly code. Now it just needs single-precision floating point instructions, and I'll draw the line there. No support for double-precision. It's not the easiest decision though, the struggle is real.

Things started going south when I decided to create my own solution for text mode display. Initially the emulator was written as a console application and I could connect to it using a terminal emulator, telnet client etc to see its output. But this felt too limiting and what modern computer doesn't have some kind of display anyway...

Since the CPU handler itself is in a separate library, I started working on a new front-end. But what should it be? I chose Windows Forms on .NET 6.0 because why not try to get on with the times, right? Or should it be WPF? Or UWP? It doesn't help that pretty much every Windows Desktop development environment you can think of is in the following state: Is it dead? Yes. Well, no, not yet, but... There is a new thing on the horizon called Project Reunion. I mean WinUI. I mean Windows App SDK. They probably renamed it since I started writing this paragraph. In that a Hello World takes from 30 to 200 megabytes and uses either a handful or a hundred individual files, depending on the build settings you chose, and then it tends not to work at all. Thumbs up guys.

I made a bare minimum application that can display text in a Rich Textbox, but it had weird screen refresh problems and worse, I realized it physically can't use an image as background, nor can it use a transparent background. For that you need WPF or UWP. Fine, I'm not going to get scared away by this, I want that background image so much that I wrote my own bitmap-based character matrix rendering control. It's beautiful and works really nicely... Unless the control is too big. Like it's in full screen on a 4K display. The update becomes just laggy. The problem isn't with the bitmap creation or font rendering itself, it doesn't have excessive CPU usage, it's just getting mangled somewhere in the bowels of Windows that's not under my control.

I tried to go between .NET 6 and .NET 4.8, thinking the issue is with the new framework, but they are equally bad. I optimized the heck out of it, it's much better than it would be by default but still not good enough. To add insult to injury, if I compile the application in x86 mode then it's fine in most cases, but in x86-64 mode the screen update gets even worse. That was a great time to figure that out, given that debugging an application in Visual Studio is still best to do in x86 mode, so the problem was always in the Release version. I also had problems with setting up a steady timer that can handle a 60 FPS update for generating Vertical Blank interrupts and deal with the screen refresh, but I solved that issue.

Right now, I feel like I wasted a lot of time with this whole text display solution. I should just make it work with a Rich Textbox control and live with a single background color.

It also doesn't help that I can't decide about a fixed character matrix size. I have various old computers and displays with different resolutions that I'd like to potentially run it on. Will it be my old Apple Cinema Display with a mechanical keyboard? Or this Dell 27" 4K display when I replace it? Or my old 13" Surface Book? Setting the matrix width to 120 and the height to something more flexible is a good solution and it's all configurable in the settings, and the programs can read the matrix size from hardware registers. Of course, it would be so much better to have a fixed size, it would work in windowed mode just fine, but I would like it to look pretty in full screen mode, where I can pretend that my hardware is running my own operating system.

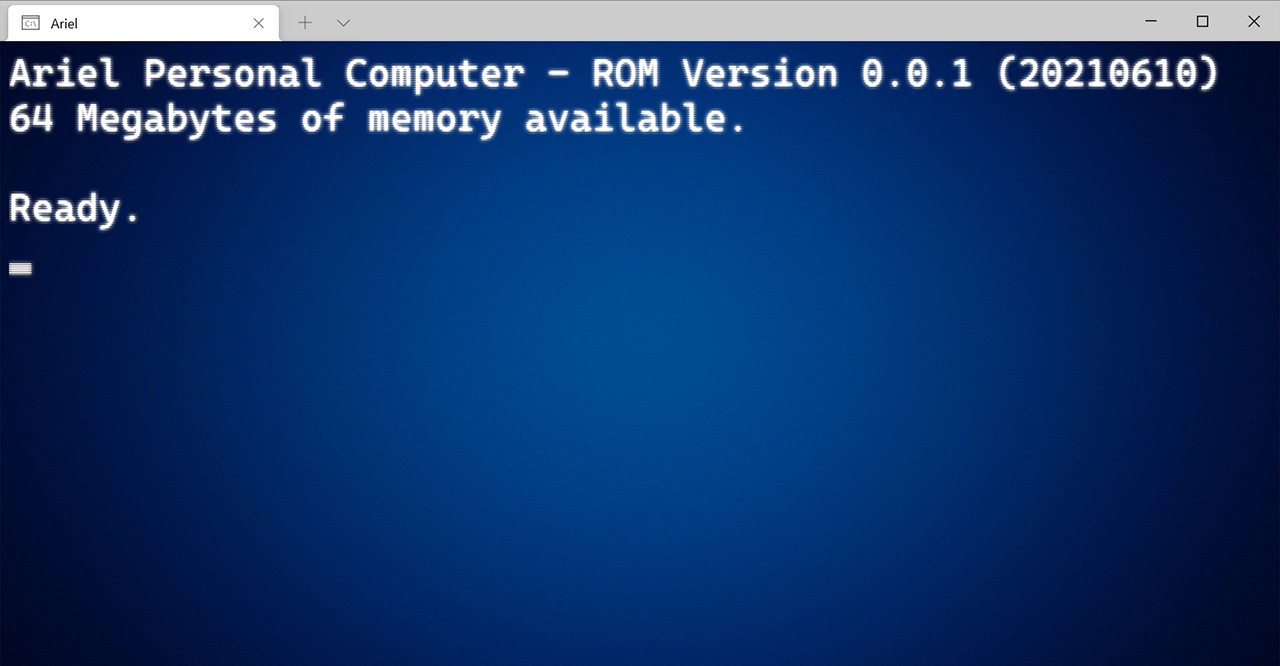

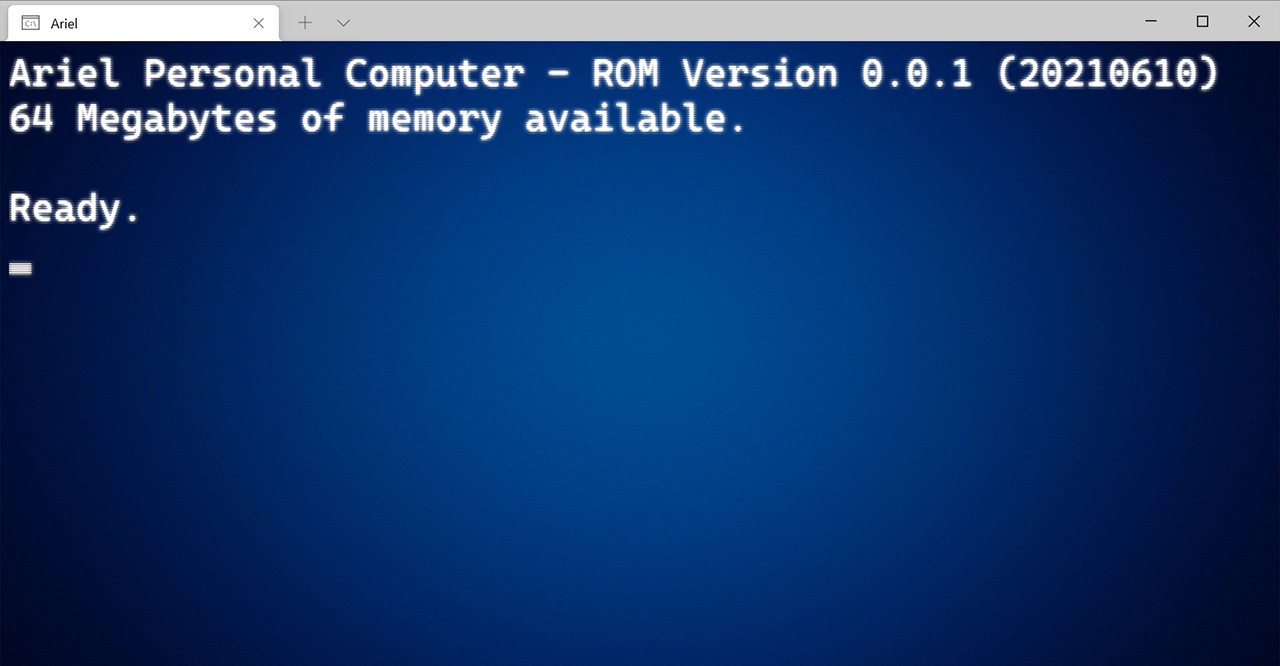

Oh, about the OS... I decided on an MS-DOS style OS that uses a Linux Bash-like shell with flexible display size, but can't do multitasking. It will just load the selected application, run it, the app can call OS Kernel functions to handle the screen, input, storage and other OS-level things without touching the hardware registers. When it's done, the program gives the control back to the shell. I made the system load a ROM image, start it up, and it loads the OS Kernel and executes it. You can type in the shell, so far so good. It does not load and execute programs yet, but I'm working on Kernel functions that programs can call.

Should I add graphics mode? It would be nice, but then I have the same problem as with the character matrix size, what will it use? 1920 x 1080 would be ideal for showing it off on YouTube, but what about all the other weird resolutions and aspect ratio my displays use? I think for the time being I will not add any graphics mode, and will see it way later whether I need it. And what about sound? Of course, I would love to write scene demos for it, but is it worth the hassle? Not really...

Mostly I want this to be a playground for making compilers and other nerdy tools that only need text display mode. At least this is a good, solid pointer that can guide my decision making about the system itself.

Take my advice, make a reasonable plan for your project and stick to it. You can always add more features to it later.

When it comes to storing information, I'm a big proponent of plain text files. If you are not, you'll understand this in just a few decades, unless you chose your file formats remarkably well. I like Notepad++ but it's quite bloated for my needs that in this case revolves around text editing and some text manipulation, and I don't need to edit code, install plugins or do anything crazy. Sometime in 2020 I started working on a lightweight text editor that is capable of multi-document editing and some text manipulation, and is also capable of opening large log files for browsing and processing.

When it comes to storing information, I'm a big proponent of plain text files. If you are not, you'll understand this in just a few decades, unless you chose your file formats remarkably well. I like Notepad++ but it's quite bloated for my needs that in this case revolves around text editing and some text manipulation, and I don't need to edit code, install plugins or do anything crazy. Sometime in 2020 I started working on a lightweight text editor that is capable of multi-document editing and some text manipulation, and is also capable of opening large log files for browsing and processing.

I've been using it ever since for daily text editing tasks, and I'm satisfied with it enough to release its first version. It's clearly for professionals and power users, so it comes as a portable package and assigning it to editable text file types is up to the user.

Features

- Supports editing multiple text files, with reopening them the next time

- Handles most modern and legacy text encoding formats and codepages

- Built-in JSON editing and formatting capability

- Offers a wide array of per-line text manipulation options

- Polished user experience

The application icon was created by the talented Miral Gosai who I highly recommend to hire for graphics design.

Features to come later

- Settings editor in the app itself, currently the settings can be edited as a JSON file, if necessary

- Workspaces for text file management, to work with multiple files in a folder structure

- Distraction-free text editing in full screen mode to write essays

- Column-mode editing, that will be added eventually using a new text rendering interface

Give it a try if you're interested in text editors, feedback is welcome and I'm open to suggestions.

Download it from the Apps page!

Platform: Windows (.NET Framework 4.8)

Recently I switched to Visual Studio 2022, the preview version. It works flawlessly for my projects, but there's still one thing I'm missing... The ability to make all #region blocks collapse in a C# source code file.

Instead of waiting for an extension to support this, or even better, for Microsoft to put this command into Visual Studio by default, I dipped my toes into IDE Extension development and whipped up one that adds the desired Collapse All Regions command into the Edit menu. This command can also be accessed by the default keyboard shortcut Ctrl-M, Ctrl-R

It can be downloaded from the Visual Studio Extension Marketplace or by using Visual Studio 2022's Extension Manager.

When I was a teenager, I only had access to a Commodore 64 at home. I envied my friends who had a PC or even an Amiga, for the seemingly unlimited RAM and crisp high resolution text display. Glorious 80 columns! At one point I wrote a Bash-like shell on my C64 with 80 character software display, each character had to fit into 4*8 pixels. It looked surprisingly good on my monochrome monitor, considering, but it was slow and I barely had any RAM left for programs to load due to all the space the shell functionality used up.

Later I got an Amiga 500 and I was happy with it text-wise, it could display a proper 640*200 screen with 80 columns of text. It was great for logging into a remote server via telnet using a modem (back then it wasn't considered harmful) where I had an account and I could use email and IRC. Writing assembly and C code on the Amiga was great and I had 1 MB RAM in it, which felt like tons. I nurtured a dream for years that I would get an Amiga 1200 with a hard disk in it and I could write a whole OS for it in assembly. That dream was never realized. When I got a proper PC I was writing programs in C. Making an OS didn't seem plausible due to the complexity of the CPU and the hardware itself. Sure I wrote some assembly code with BIOS interrupt calls but making anything serious as bare metal code is pretty hard on a PC, especially these days.

A few years ago I thought the Raspberry Pi will be great for such aspirations, but while the ARM CPU itself is OK to code for, the hardware is just way too modern, and in the same time surprisingly badly documented. Sure, making the Status LED blink was doable, but even that has sailed with the Pi 4 as I heard. Putting text on the screen is hard due to working in graphics mode (good luck even making a frame buffer with all those badly documented mail slots), accessing the SD card is hard, writing a whole FAT32 file system driver is really hard, writing a USB driver for keyboard handling is super hard. Using the GPIO pins to access the Pi via serial port is doable, but then you are still just using a terminal program to access a box, and for every change in the kernel code you need to copy data to the SD card and reboot, or use QEMU for everything, and... Small wonder that most "Let's make an OS for an ARM SBC" projects die at the stage of a blinking LED.

Some dreams come true

My dream computer would use a 32-bit CPU that is similar to ARM, but less complicated to work with, so it's somewhere between the 6502 and the ARM V6. Lots of RAM, up to 4 GB due to the 32-bit address space, but realistically I would never need that much. Easy enough access to the hardware using Hardware I/O registers. Unified memory architecture if I would ever have video and audio in it. A smart disk controller device that would give access to the file system in a high level way, so its firmware would handle the complicated block level tasks. A serial console port solution to access the system using a terminal program.

Since nobody is going to make it for me, and I'm just a software guy, I decided to make my own computer as a virtualized entity. It's called Ariel.

I created a small Virtual Machine in C# that can run a RISC CPU I designed and some virtual hardware devices I made. The ARM-like CPU is something that would work in real life, it could be implemented as an FPGA core, and the devices are either realistic or plausible. The VM can run code over 12 MIPS (million instructions per second) on my PC; this is comparable to a speedy Intel 486. Plenty of power for my needs, I would be fine with just 1 MIPS, and it's not particularly optimized code. Also this is just a number, I believe the Ariel CPU packs a bigger punch than a 486 when it needs to run useful code.

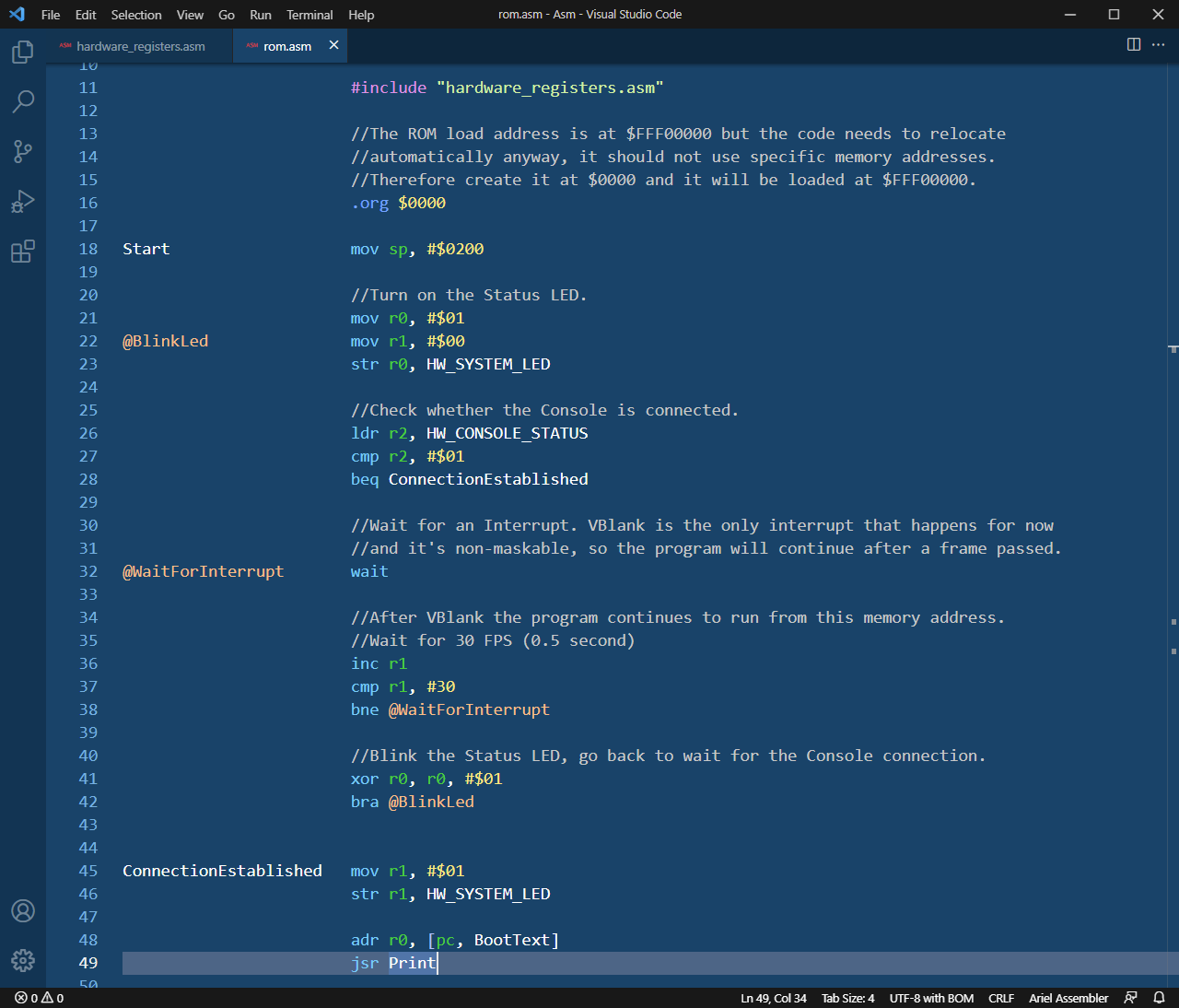

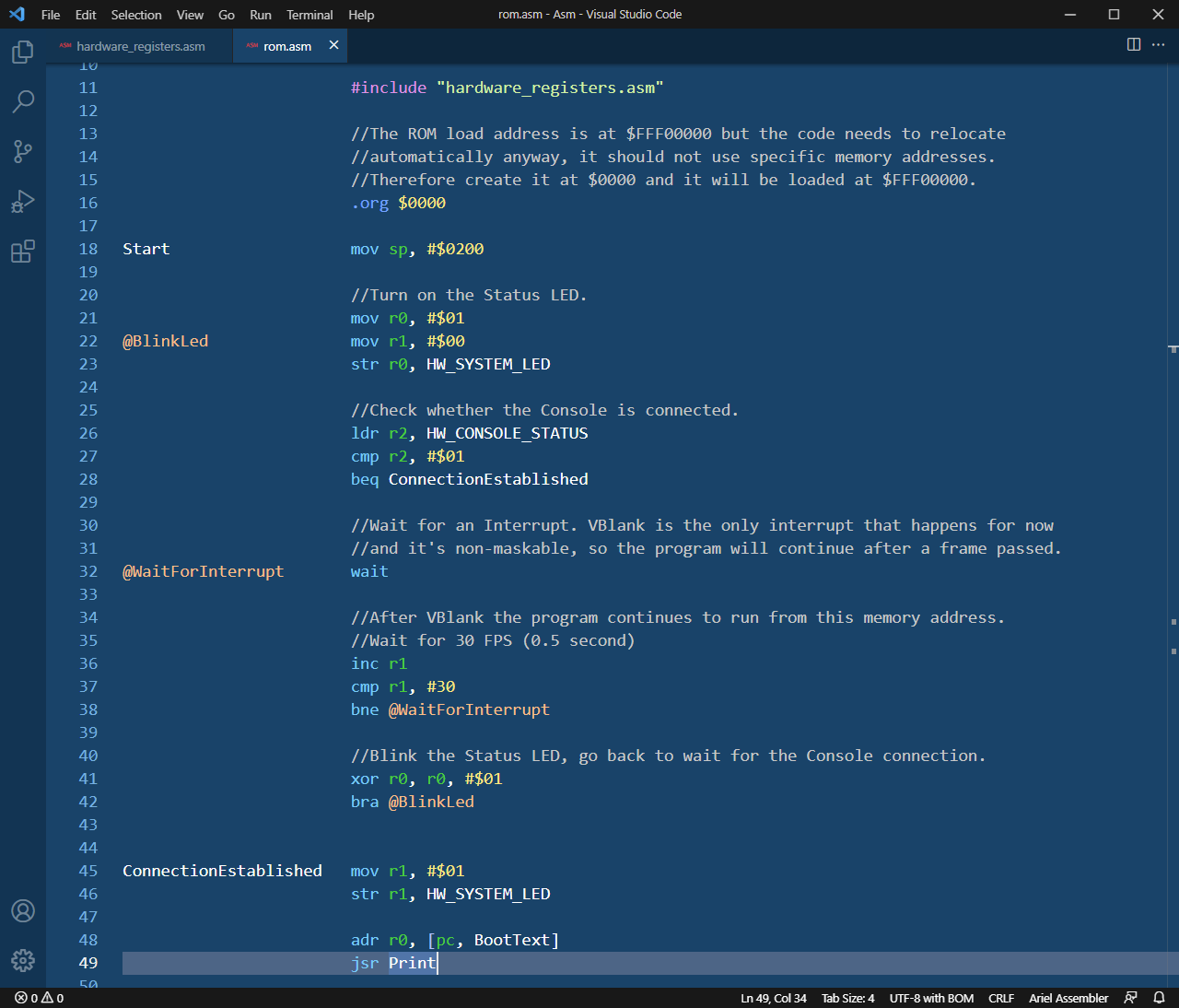

I wrote my own assembler for it, along with a Visual Studio Code extension. It works like a charm, in some aspects it's even better than Retro Assembler. Ariel boots a ROM image that is really simple so far, and afterwards the ROM will load the Kernel from the file system. The RAM size is configurable, it can be up to 4095 MB. The top 1 MB is the Hardware Space, and the top 64 KB is the Hardware I/O Space for the hardware registers that give me access to devices. The VM emulates the serial console port using a TCP Socket, so I can connect to it via Telnet on a specific port, even via the Internet.

What is it good for?

- Primarily it's for me. Making my own CPU and hardware devices, albeit virtually, is a great challenge and fun for an engineer. I enjoy it immensely and I haven't played with many video games since I started this project.

- I made an assembler for it, that was and still is a really enjoyable pastime.

- I can write my own ROM for it that already starts the computer and allows for terminal communication.

- I can write my own OS for it, finally.

- I can write interpreters or compilers for various languages like Basic and Python, and I can even write a small C compiler, because compilers are fun to make. Making those to create x86 or ARM code is hard and realistically nobody else would use them, so I might as well just generate code for my own CPU.

- I can write a C# -> IL -> Ariel Assembly compiler so I can write complex applications for it in Visual Studio, if I choose to do so.

- Later I can add a video device to it and even audio.

- Others who would like to dabble with writing bare metal code in assembly, ROM code or even a kernel, could use it and enjoy working on it, without the endless frustration of using real modern hardware.

- I plan to put it on GitHub when it's a bit more mature, so others could contribute, or even modify it for their own needs if they want to.

- Somebody could just make a ROM that starts up a Basic interpreter, like in the Commodore 64. I might be that somebody, some day.

If you're interested in this project, and would like to try it later, and perhaps even would like to write some code for Ariel, let me know what you think on Twitter. I would appreciate it. I'll follow up on how this project is going when there's more to share.

Now that we reached a new year and Microsoft is consolidating .NET Core and the .NET Framework into a merged version, Retro Assembler is now built for .NET 5.0

After you install it on Windows, macOS or Linux, you can run the assembler just like you did before. Or if you're new to it, check out Using Retro Assembler with Visual Studio Code for some additional guidance.

If you've been following the MEGA65 development in the past few years, you might be as excited as I am that it will be available for purchase soon. Quite possibly, maybe. But now that at least some lucky people laid their hands on the limited developer version, you may find it useful that Retro Assembler got support for the MEGA65 45GS02 and the plain CSC 4510 CPUs. Nothing can stop you now from developing for the MEGA65!

Beside this I attempted to standardize the 65816 source code a bit, so in instructions that use the Stack Pointer, the assembler accepts both SP and S as register name. The disassembler now shows SP.

The Notepad++ language files and the Visual Studio Code Extension got support for the new CPUs and for the SP register.

See the documentation for details.

Download the latest version from the Retro Assembler page!

If you want to use Retro Assembler to code on Linux (even on a Raspberry Pi) or on macOS, you have to install .NET on your computer. The current version is .NET 5.0 This used to be called .NET Core in previous versions, but Retro Assembler doesn't support those anymore. Normally you'd just go to https://dotnet.microsoft.com/download and follow the instructions, but if you need help, I'll try to provide some here. Especially for ARM-based single board computers, see below.

Disclaimers

- During the time of writing this guide, the current .NET version is 5.0.2

- If there is a newer version by the time you read this, install that one.

- Only the .NET Runtime is needed to run applications like Retro Assembler therefore this guide focuses on that option.

- This guide assumes you use Ubuntu Linux 20.10, or any of the recent macOS versions on Mac.

- This guide assumes you use the Bash shell which is the default on most systems.

- If you mess up something in your system, don't hold me responsible. But you should be just fine.

Installing on Windows

Installing on macOS

- Go to the .NET download page, choose macOS on the top.

- Download the full .NET SDK installer.

Installing on Linux

- Go to the .NET download page, choose Linux on the top.

- Click on the Install .NET button and on the page it opens, scroll down to your chosen Linux distribution and version. Or here is a direct link to the Ubuntu 20.10 page which lists the installation steps.

Here are the commands you'll need to enter into the Terminal:

#Download the Ubuntu 20.10 related packages for the package manager.

wget https://packages.microsoft.com/config/ubuntu/20.10/packages-microsoft-prod.deb -O packages-microsoft-prod.deb

#Install it for the package manager.

sudo dpkg -i packages-microsoft-prod.deb

#Update the package manager.

sudo apt-get update

#Install this utility.

sudo apt-get install apt-transport-https

#Update the package manager (again).

sudo apt-get update

#Install the .NET Runtime.

sudo apt-get install dotnet-runtime-5.0

#Alternatively, Install the full .NET SDK

sudo apt-get install dotnet-sdk-5.0

Installing on Raspberry Pi and on other ARM based SBCs

- Go to the .NET download page, choose Linux on the top.

- You'll need to download the ARM32 binaries package and install it manually. Click on All .NET downloads..., pick the latest version and in the Run apps - Runtime column (on the right side) find the .NET Runtime (version) section. Download the ARM32 package from the Linux Binaries.

- Here is a direct link to the now-latest version ARM32 5.0.2

- If you use a 64-bit OS, you may need the ARM64 package.

- Rename this downloaded file to dotnet.tar.gz for easier handling below.

Here are the commands you'll need to enter into the Terminal:

#Install some possibly missing packages that will be needed.

sudo apt-get install libunwind8 gettext curl wget

#Make the dotnet directory where the .NET Runtime will be installed.

sudo mkdir /usr/share/dotnet

#Extract the files from the downloaded file.

sudo tar -xvf dotnet.tar.gz -C /usr/share/dotnet/

#Set up a symbolic link to this directory so it will be found on path

#when you type in the command "dotnet".

sudo ln -s /usr/share/dotnet/dotnet /usr/local/bin

This works perfectly, the only caveat is that you'll need to perform this manual install with every updated .NET version you want to use.

Testing in the Terminal

Run this command to check whether the .NET Runtime has been installed successfully. It will list the currently installed version's details.

dotnet --info

Now you can run Retro Assembler with this command:

dotnet retroassembler.dll

Optional, but it is recommended to edit the command shell's startup file with a command alias to run Retro Assembler with ease, as if it was a Linux/Mac native command line application.

Open your user's home directory and edit the hidden file .bashrc on Linux, or .bash_profile on macOS. The latter usually doesn't exist and you have to create it. Then enter this line into the bash file with your chosen file path:

alias ra='dotnet ~/PATH/retroassembler.dll'

This will allow you to just enter the command ra and run the assembler from either the Terminal or from Visual Studio Code.

The following updates have been made:

Empty Macros get removed from the compiled code automatically. These caused some local label issues.

When the Setting OmitUnusedFunctions is Enabled, empty Functions and their standard, correctly formatted calls get removed from the compiled code.

When the Setting Debug is Enabled, a text representation of the compiled code is saved alongside with the normal debug information. This way you can check out your compiled file's code and data contents, without doing Disassembling which would not recognize the data sections. You can change its default filename in the Setting DebugCodeFile or in the Settings Xml file.

When the Setting OutputSaveInfoFile is Enabled, now Atari DOS (.xex) files create the Info file about memory usage. The Atari 800 example file has been updated to utilize this feature.

See the documentation for details.

Download the latest version from the Retro Assembler page!

This is a quick update for to fix a nasty little bug in the parser and compiler.

The problem was with the number size detection of currently-undefined labels. An lda <Label or lda >Label instruction, or similar ones using a zero page address would process the memory address of Label incorrectly, when Label is defined after the instruction's code line.

Friend of the project, John Tsombakos was kind enough to write up a reproduction case about it. Thank you John!

See the documentation for details.

Download the latest version from the Retro Assembler page!

The following changes have been made since the last update:

- New Setting DefaultScreenCode added to control the encoding Type and Case that the ".stext" directive uses for character code conversion.

- The Setting OmitUnusedFunctions is no longer Enabled by default to avoid issues with existing source code. It can be enabled on demand.

- When a file is included using the .include or the .incbin directive, the file's Directory is automatically added to the list of Known Include Directories. This way a file loaded with full path can include subsequent files without specifying the full path of those nested files.

- Long Branch Handling now works within Macros, too.

See the documentation for details.

Download the latest version from the Retro Assembler page!

When it comes to storing information, I'm a big proponent of plain text files. If you are not, you'll understand this in just a few decades, unless you chose your file formats remarkably well. I like Notepad++ but it's quite bloated for my needs that in this case revolves around text editing and some text manipulation, and I don't need to edit code, install plugins or do anything crazy. Sometime in 2020 I started working on a lightweight text editor that is capable of multi-document editing and some text manipulation, and is also capable of opening large log files for browsing and processing.

When it comes to storing information, I'm a big proponent of plain text files. If you are not, you'll understand this in just a few decades, unless you chose your file formats remarkably well. I like Notepad++ but it's quite bloated for my needs that in this case revolves around text editing and some text manipulation, and I don't need to edit code, install plugins or do anything crazy. Sometime in 2020 I started working on a lightweight text editor that is capable of multi-document editing and some text manipulation, and is also capable of opening large log files for browsing and processing.